By Thiago Cintra Oppermann

PART I

Most people in Papua New Guinea know where Mendi is. The city, nested amongst the mountains of the Southern Highlands, has a permanent population of around 30,000 which ebbs and flows as people visit the regional centre to carry out business. It would be surprising if someone drew a map of the Highlands and forgot to include the Southern Highlands or its capital. Many people, particularly if they are interested in elections, or paid attention at geography classes, will answer that Mendi is situated in the electorate of Mendi-Munihu Open. This is certainly what I would have answered.

Surprisingly, this answer is not correct. Mendi is not in the electorate of Mendi-Munihu. It used to be there, but not anymore. The town has not moved, but the boundaries of Mendi-Munihu have. This took place in 2022, when a new set of electorate maps were approved by Parliament. There is no shame in not knowing this, as the change to Mendi was not publicised. Indeed, the inhabitants of Mendi — who would go on to cast votes for Mendi-Munihu Open candidates in 2022, after the town had been removed from that electorate — might be even more surprised. So what is the real answer?

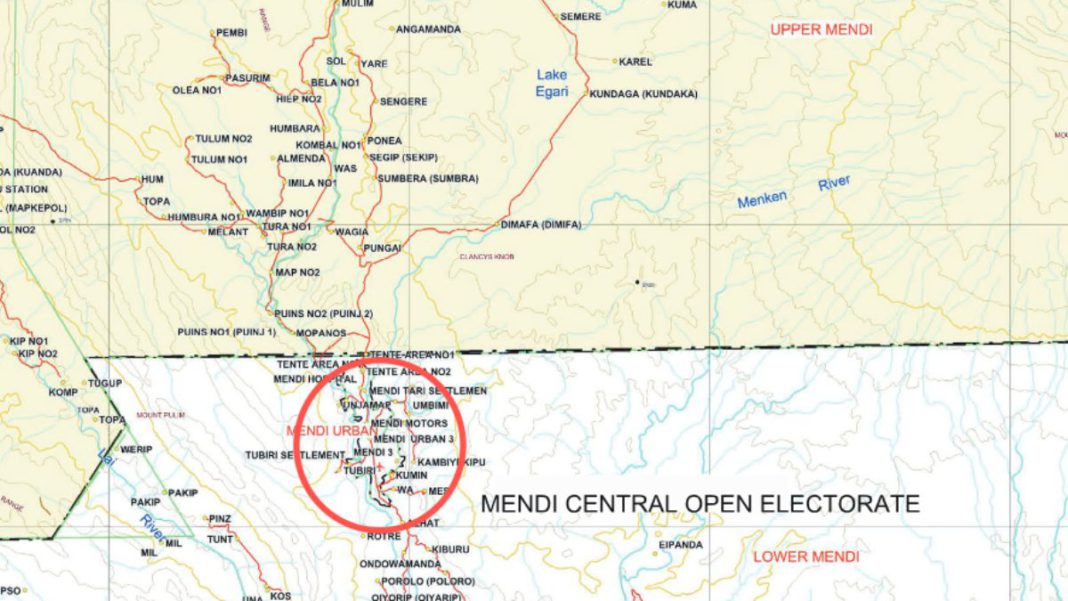

Figure 1: Imbonggu Open electorate Map

Mendi urban area indicated by red circle

Source: PNG Electoral Boundaries Commission

Figure 2: Mendi-Munihu electorate map

Mendi urban area indicated by red circle

Source: PNG Electoral Boundaries Commission

The answer to the question is unsettling: Mendi is not in any electorate. In Figures 1 and 2 we see the maps the electorates north and south of Mendi. To the south is Imbonggu (Figure 1). The red circle shows the Mendi urban area, outside of that electorate. To the north is Mendi-Munihu (Figure 2). The red circle again shows Mendi, outside the electorate. The maps differ in an important way. The Mendi-Munihu map has a southern border with “Mendi Central Open Electorate”, an electorate and district that does not exist yet, but is supposed to come into being in 2027. Imbonggu, on the other hand, has a northern border with Mendi-Munihu as it was before its redefinition.

These are not just any maps. These are the actual maps approved by the National Parliament when they accepted the recommendations of the Electoral Boundaries Commission (EBC) for creating new electorates in 2022. There is clearly a serious error here, a gap, and the entire town of Mendi, along with its environs, fell into it.

Mendi is not alone in finding itself in a gap in the new electoral map, and conversely, there are many more places which are currently assigned to more than one electorate. In two recent papers for the Department of Pacific Affairs In Brief series, Professor Nicole Haley and I outlined the basic problem, and the difference between PNG’s map of electorates and districts as they are established by law, and the map of these districts as they are organised in practice.

Papua New Guinea’s electorate map remained mostly unchanged between 1977 and 2022. In 2011, two new Provincial electorates were created for the new Jiwaka and Hela provinces, but the underlying Open electorates were not altered. Papua New Guinea’s constitution makes alterations to electorate boundaries very difficult, necessitating a report by the Electorate Boundaries Commission and approval by Parliament. This makes the electoral map resistant to political interference or gerrymandering, but it also makes it resistant to any change. Over a period of 45 years, serious issues of malapportionment accumulated, with the difference between the most and least populous electorates far outside the range prescribed by legislation. It was generally agreed that something had to be done about it.

In 2022, Papua New Guinea’s parliament approved the formation of 13 new electorates. Seven of these were implemented for the 2022 election and another six were approved for the 2027 election. These new electorates will not solve the issue of malapportionment. Indeed, some of the new electorates created are “born noncompliant”, with populations above or below the quota. The redistribution was also approved only a few months before the 2022 election, leaving little time to implement the changes. Nevertheless, the change to electoral boundaries was generally welcomed and seen as a step in the right direction.

It has, however, proven very challenging to find out what the redistricting really did to the electoral map. Unusually, the published report of the EBC did not include any maps or descriptions of boundary perimeters. Instead, the report defines the new electorates in terms of Local Level Governments and Wards. This is quite problematic, as LLGs boundaries are more vulnerable to political pressure, while Wards are points with no geographical extent. Drawing a map of an electorate using Wards would be like trying to draw a map of a country using only its cities.

This left researchers speculating on the proper placement of the new electorate boundaries. In most cases, the creation of the new electorates involved splitting existing electorates: the external boundary between the new electorates and others should not have been altered. Most people believed that the redrawing of the electoral map was limited to these changes. Nothing in the Electoral Boundaries Report would lead a reader to suspect otherwise.

At the end of 2024, we were able to track down the set of maps that were submitted to Parliament in the Parliamentary Library. As it turns out, the new electorate map includes far more changes than is commonly understood. Indeed, there were changes to a majority of electorates, with electorate boundaries altered in nearly every province. Only the changes within the electorates that were split were discussed in the EBC report or debated in Parliament.

In several of the changed areas, the new boundaries have plausible impacts on electoral politics, yet they were adopted without public discussion. Indeed, given the difficulty in accessing electorate maps it is quite likely that the majority of the alterations remain at present unknown to the populations affected. While the lack of transparency in this process is concerning, the full set of issues stemming from this new electoral map is in fact considerably more serious: the new map set is inconsistent and contains numerous drafting errors.

PART II

The new set of Electoral Boundary Commission (EBC) maps accepted by Parliament in 2022 not only makes unannounced changes, but also creates inconsistent boundaries between many electorates. Some areas are assigned to more than one electorate, while others are not assigned to any electorate. The latter include large, densely populated areas such as Unggai Local Level Government area in the Eastern Highlands and — astonishingly — the Mendi urban area and its environs in the Southern Highlands.

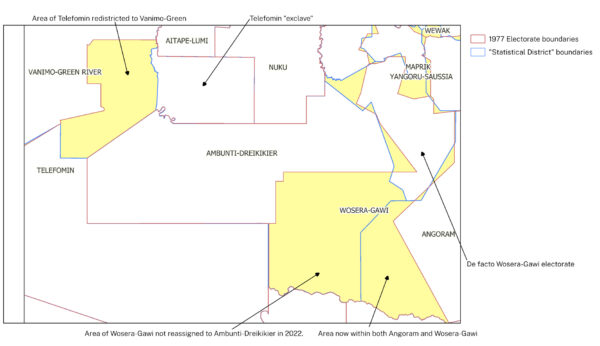

Figure 1 shows a map of PNG where we have superimposed the 1977 electorate boundaries and the National Statistical Office (NSO) map of “statistical districts”, the main source for the unannounced changes in 2022. The difference between the maps is highlighted in yellow. As can be readily seen, these are quite substantial. The box in Figure 1 is expanded in Figure 2 to give an example of the resulting situation in West Sepik (Sandaun) and East Sepik Provinces.

Figure 1: 1977 electorate boundaries and current statistical districts

Source: Oppermann and Haley. 1977 Electorate boundaries layer supplied by ANU CartoGIS.

Figure 2: West Sepik (Sandaun) and East Sepik Provinces showing 1977 electorate boundaries and current statistical districts

Source: Oppermann and Haley. 1977 Electorate boundaries layer supplied by ANU CartoGIS

In West Sepik (Saundaun) province, Telefomin was in created in 1977 as an approximately “C” shaped polygon. The NSO map differs, such that an area of Telefomin is shown as part of the Vanimo-Green “statistical district”. The 2022 redistricting reassigned that section of Telefomin to Vanimo-Green. This renders Telefomin discontinuous, but at least both maps fit together, as the 1977 electorates were replaced with NSO geometry throughout. Such a complete replacement was also carried out in some other provinces, for instance Madang.

In East Sepik, the replacement is not complete, creating inconsistencies. Wosera-Gawi is a large electorate, shaped a bit like an hourglass in the 1977 map, but a much smaller “rump” in the NSO map. In this case, the 1977 map of Wosera Gawi was not changed in 2022. However, the 2022 mapset includes the NSO version of Angoram. In this NSO version, Angoram shares a border with Ambunti-Dreikikier – the blue line running down the middle of the southern portion of the 1977 Wosera-Gawi electorate.The yellow area east of this line is now assigned both to Wosera Gawi and to Angoram on their respective pages of the 2022 mapset. Ambunti-Dreikikier, to the west of Wosera-Gawi, was not changed, so its map does not show a border with Angoram. However, examination of the polling schedule shows that the part of Wosera-Gawi electorate within the NSO boundaries of Ambunti-Dreikikier “statistical district” in fact polls in Ambunti-Dreikikier. “Statistical districts” are in practice a closer approximation of Papua New Guinea’s actual administrative borders than the electoral map, including in matters of electoral administration.

There are many more similar cases, and others which are more complex as they combine maps from multiple sources. The Jiwaka-Western Highlands boundary near Anglimp is particularly complex, with at least three different, inconsistent source maps, some of which disagree with the provincial boundary. This is an important detail, as the provincial boundary has a separate definition and was not altered in 2022.

To appreciate the scale of the potential problems arising from this, we must consider two aspects of Papua New Guinean law. First, it is important to stress that the new set of maps is not simply a “bad representation” of electorates. They are the very definition of the electorates. It is this definition that has been, in many cases, broken. The Supreme Court of PNG has determined that the boundaries of open electorates are established on the basis of the maps and descriptions tendered with EBC recommendations, once these are approved by Parliament. Parliament, in turn, may approve or reject an EBC report, but not amend it. Therefore, the vote in 2022 approved all the maps, including those with unannounced changes, and those which are inconsistent.

Second, electorates have two essential functions. They are the foundation on which elections are run. Prior to the redistricting, there was already a widespread problem that the polling schedule followed “statistical districts”. This issue has earned the PNG Electoral Commission reprimands from the Supreme Court in the past. Now the matter is considerably worse, with large areas for which there is no answer as to what, if anything, the true electorate is.

However, the function of electorates in the structure of the Papua New Guinean state goes beyond elections. Section 72(4) of the 1995 Organic Law on Provincial Governments and Local-Level Governments (OLPGLLG) established that the boundaries of a district are those of the electorate. Before 1995, electorates and districts had entirely distinct maps, but after 1995 electorates and districts should have become coterminous.

The origins of the current problem can be traced in part to the failure to implement this change in definition. This would have required either redistricting electorates to match administrative realities after 1995, or else an updating of the administrative maps to match the electorates. Instead, multiple maps continued to be used, of which the NSO is the most common. This map has by now been adopted by Google Maps, Open Street Maps, the United Nations Humanitarian Data Exchange and some but not all Wikipedia pages. (The difference between the maps is readily apparent from the shape of the Western Highlands-Jiwaka border, correctly represented here.)

In 2022, the uneasy coexistence of different district maps circled back to disrupt the very maps that define districts. We are now faced with the situation where in many cases electorate and therefore district boundaries overlap, and some cases in which areas are not legally in any district. The potential implications of this are disquieting. Districts are a keystone of Papua New Guinea’s public administration and financing. It is very much unclear how, for example, District Service Improvement Program funds could be spent in an area not legally in any district, or who has responsibility for maintaining services in areas that are now in more than one district. Possibly, the incoherence of the maps will be ignored – but this is yet another step towards the informalisation of Papua New Guinea’s state, and a potentially dangerous one.

What is to be done? The 2022 redistricting effort has inadvertently created a situation in which it may not be possible to carry out basic government functions, such as elections and provision of services, in full compliance with the law. It requires urgent attention.

There is only one way to solve the problem, and that is a Parliamentary vote approving a new, corrected set of maps. An opportunity for a relatively straightforward fix exists because the map set approved in 2022 only includes the electorates for that year’s election, but the EBC report establishes also electorates for 2027. This will require a new set of maps, and when these are approved, corrections can be made. Some of the most serious problems, such as Mendi’s not falling within any electorate, would be solved in quite a straightforward manner, since Mendi Central Open Electorate, which will include Mendi urban area, is slated to be established in 2027. Other inconsistencies, however, would require a choice between different maps. Such choices are never without political implications.

A more lasting solution, however, would require a full EBC report — at which time other serious issues concerning PNG’s electorates could be addressed, notably malapportionment and the impracticality of the 1977 boundaries under current administrative and political configurations. Such work would be demanding, expensive and time-consuming. But if there is one lesson to be learned from the broken 2022 electoral map, it is that utmost care and diligence must be applied to safeguarding this essential foundation of PNG’s political and administrative infrastructure.

This article was first published in the Australian National University’s DevpolicyBlog and has been republished here with the kind permission of the editor(s). The Blog is run out of the Development Policy Centre housed in the Crawford School of Public Policy in the ANU College of Asia and the Pacific at The Australian National University.

Note: View the ANU Department of Pacific Affairs In Brief papers published by Nicole Haley and Thiago Cintra Oppermann on the problems arising from the 2022 electorate map, and the difference between PNG’s map of electorates and districts as they are established by law, and the map of these districts as they are organised in practice.

Disclosure: This research was supported by the Pacific Research Program, with funding from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views are of the author only.

Contributing Author: Dr Thiago Cintra Oppermann is a research fellow at the Department of Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. He is an anthropologist working on the history and social organisation of Bougainville, and electoral politics in Papua New Guinea.

Support Our Journalism

The global Indian Diaspora and Australia’s multicultural communities need fair, non-hyphenated, and questioning journalism, packed with on-ground reporting. The Australia Today—with exceptional reporters, columnists, and editors—is doing just that. Sustaining this requires support from wonderful readers like you.

Whether you live in Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, the United States of America, or India you can take a paid subscription by clicking Patreon