By Amantha Perera

“We will burn down the Fiji Sun.” You sit down to start your workday and this is the first thing that flashes across your screen. Will you stay on and do your job as a reporter or consider fleeing?

The tone and the content have become familiar to Iva Nataro, a senior journalist at the Fiji Sun newspaper.

“People go to the extent of saying we will burn down the Fiji Sun office including everyone in it. They actually post this online. For a couple of times, we had to inform the police that we have been receiving these kinds of threats.”

Nataro’s experience is not the exception. In fact, threats, abuse and other forms of harm communicated using online or digital interfaces have proliferated in the last decade. These hazards, grouped under the term technology-facilitated threats (TFTs), have increased in number and the content has worsened in severity since the COVID-19 lockdowns and the pivot to remote working.

My work at the Centre for Journalism and Trauma Asia Pacific (CJT) and Adelaide University provides me with a microscopic view of how these hazards are playing out and their telling impact on those who are exposed.

We have heard incidents of colleagues mocked online for what they wore while on camera or while live streaming on Facebook. Others have recounted how their names and other details were doxed, or posted online, after they investigated the release of intimate images of public figures. The investigations by the journalists ultimately proved some of the images were fake.

“Honestly, we are exposed every day because of the line of work that we do,” Nataro told me recently.

When they are exposed to TFTs, journalists often lack the skills and training to effectively assess them. They are caught unawares.

Often, the exposure takes place on platforms where they share professional content alongside personal engagements. Because of the way social media functions, exposure can be cyclical and take place whenever and wherever online connectivity is established.

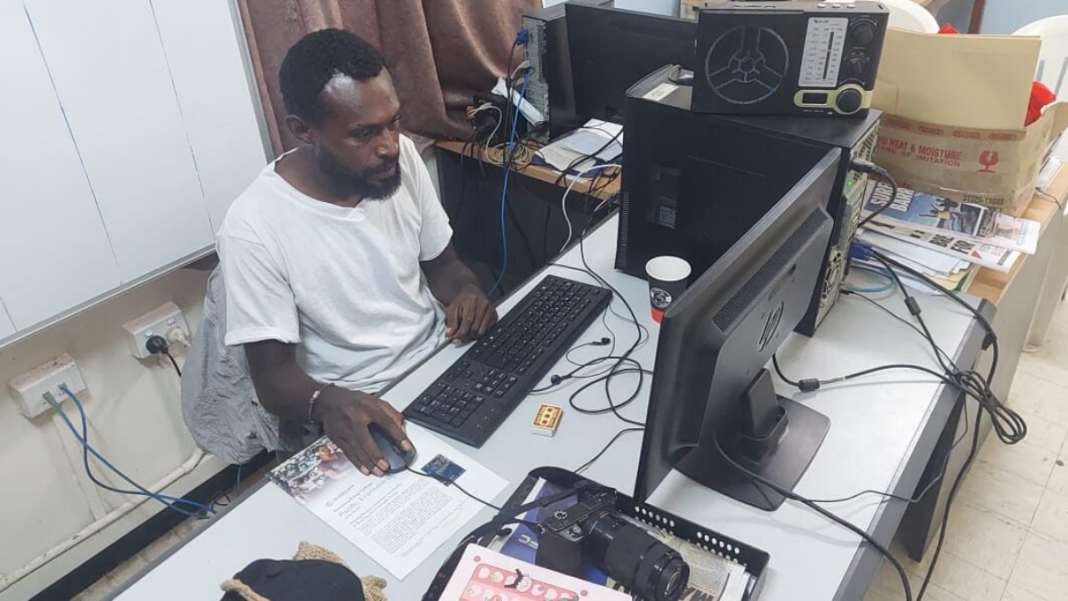

Furthermore, those like Nataro and Irwin Angiki, the editor of The Island Sun newspaper in Solomon Islands say that the close-knit nature of their communities adds new layers of complexity to TFT exposure. The chances of journalists’ knowing the source of the threat is high, even where posts are anonymous. Their communities expect the journalists to act as gatekeepers. But the reactions they get can be divisive and, at times, hateful. A Vanuatu journalist said:

“Sometimes when you go to church on Sunday, you meet everybody, the politician, the police chief, the influencer … and they all expect you to be the journalist and nothing else.”

When exposed to a relentless cycle of online dangers without the skills to mitigate them, journalists are left feeling overwhelmed and unable to execute their professional duties effectively.

Angiki spoke of the persistence of the “bullet-proof” approach to journalism which was preventing journalists from addressing these concerns with transparency.

“Big majority of them – they are what we call thick-skinned. They don’t display that much of effect or hurt or pain from online abuse.”

When the exposure and impact becomes too hard to handle, exposed journalists resort to removing themselves from, or silencing themselves in, online spaces.

“I’ve had some really junior colleagues who have reached the extent of wanting to leave the media industry, they have experienced such online abuse or online bullying to the extent that they want to leave the Fiji Sun and stop being a journalist altogether,” Nataro said.

Even if they remain, their journalism can suffer. Angiki related the experience of a junior colleague whose work deteriorated due to online trolling. She wanted to “change beats”, or move away from the sector of the community allocated to her for reporting, when confronted with waves of abuse and threats. Angiki and other colleagues dissuaded her.

“She went back. But then you noticed her stories were briefer. We noticed details contained less character — the government said this, the government said that. More like parroting, which was safer than what attracted these online idiots. So, yeah, it affected the way she wrote her stories. It was just straight parroting,” he said.

Research shows that females and journalists from minority communities are exposed to higher levels of digital hazards.

CJT has been leading efforts in the region to provide skills to journalists in the Pacific region to tackle TFTs. Nataro and Angiki have taken part in the CJT AsPac Fellowship which provides introductory awareness training on trauma-informed journalism. They also played significant roles as fellows in the innovative 2024 fellowship on tackling Technology-Facilitated Gender Based Violence. Angiki said:

“Back here we associate trauma with serious stuff like death, serious accidents. [But] we’ve never associated our work, journalism, with trauma. When I brought back what I learned from Brisbane and shared with my reporters, it was a big shake-up, like we woke up.”

TFTs are dynamic and quickly adapt to socio-political trends. With the wide and easy use of AI technology, they can be scaled up, infused with fakes and misinformation which makes them hard to track. Newsroom leaders we have worked with from the Pacific talk of their own sense of vulnerability when they find it hard to deal with exposure in their newsrooms.

The threats are unlikely to ease any time soon. In fact, they could ramp up.

Meta has announced that it is considering expanding community notes outside of the US. The blueprint it plans to use is X’s own adoption of community notes in place of moderation. If Meta goes ahead with its plans without proper guardrails, Facebook, Instagram and Threads will soon turn into versions of X.

The proliferation of TFTs has shown us that the digital hazards to which journalists are exposed easily seep through generic interventions aimed at slowing them down. Threats have to be contextualised within the information space in which they manifest. The journalist who is facing the exposure has to be placed right at the core of any threat analysis and efforts at prevention.

Disclosure: The Centre for Journalism and Trauma Asia Pacific was previously known as the Dart Centre Asia Pacific. The 2024 Technology-Facilitated Gender Based Violence fellowship received funding support from the Google News Initiative.

This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University.

Contributing Author: Amantha Perera is a researcher, academic and writer currently based in Australia. He is in the final stages of a PhD candidature at University of South Australia and a director and consultant at the Centre for Journalism and Trauma Asia Pacific, formerly known as the Dart Centre Asia Pacific.

Support our Journalism

No-nonsense journalism. No paywalls. Whether you’re in Australia, the UK, Canada, the USA, or India, you can support The Australia Today by taking a paid subscription via Patreon or donating via PayPal — and help keep honest, fearless journalism alive.