By Omer Ghazi

The United Kingdom has, in recent months, witnessed mass anti-immigrant protests – a turbulent outpouring of anger that, while definitely being marred by some xenophobic rhetoric, is, at the same time, rooted in grievances the state has long failed to address. At its core lies a simmering resentment that has been building for decades, rooted in the state’s abject failure to confront uncomfortable truths, chief among these are the grooming gang scandals — most infamously in Rotherham, Rochdale, and Telford — where men of predominantly Pakistani heritage orchestrated systemic abuse of vulnerable British girls, some no older than ten.

Baroness Louise Casey’s 2025 audit confirmed what had long been whispered: in towns across Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire, Pakistani-heritage men were disproportionately represented in such cases, with over 4,200 instances recorded in recent years. Yet, the language deployed while referring to those involved — “Asian grooming gangs” or “South Asian men” — was carefully chosen, blurring specificity and casting a shadow over Indian, Bangladeshi, and other Asian communities, who often find themselves unfairly tarred with the same brush, despite not being involved in these atrocities.

It Is also a grave disservice to communities like Indian Muslims, who in fact embody the sharpest rebuttal to the so-called “Muslim problem” narrative. Not only have Indian Muslims consistently avoided any association with grooming gang scandals or demands for Sharia enforcement, but they also model civic integration in striking ways.

Recognizing and maintaining this crucial distinction isn’t political correctness, it’s accuracy. There have been instances of friction between the Muslim communities from India and Pakistan as well – a very good example is a recent video from the eve of India’s Independence Day in East London, where a Muslim girl of Indian origin, dressed in a hijab and carrying the Indian flag, was harassed and jostled by a group of Pakistani men.

Moreover, phrases like “Asian grooming gangs” and “South Asian men” also reflect poorly on the larger Indian community in the United Kingdom as well, who are anything but a liability. A new report by a British think tank, Policy Exchange, says Indian-origin people in that country lead all ethnic minority groups on all socio-economic and developmental parameters, often doing as better, if not more, than the resident white population.

At nearly two million strong, they are the most successful ethnic minority in the UK, with more than 40% working in professional sectors, 71% having their own homes, and their businesses contributing upwards of £37 billion to the economy and sustaining more than 170,000 jobs.

This is not a community plotting to impose Sharia law or carve out enclaves of separatism. It is, in fact, one of the most integrated and aspirational immigrant groups in Britain — a living proof that the story of immigration is not a singular tale of strain and resentment, but also one of success and contribution.

Across the Atlantic, the United States is also experiencing a surge of anti-immigrant sentiment, though of a distinctly different variety. There, the rhetoric is less about cultural imposition and more about economic anxiety — immigrants framed as competitors for jobs, housing, and social benefits. Border politics dominate the conversation, with record numbers of crossings at the southern frontier fuelling claims that the system is “out of control.” Politicians from both the parties have capitalized on these fears, though in different registers: Republicans warn of a nation being “overrun,” while Democrats struggle to balance humanitarian commitments with voter unease in swing states.

The discussion around immigration in the US is completely different, where the commentators are struggling to differentiate between illegal immigrants jumping the fence in search of greener pastures and highly-skilled, educated individuals legally relocating and becoming net contributors to the economy. Yet the narrative of scarcity and threat has proven far more persuasive in the age of populism, turning immigration into a litmus test for what it means to be American in the 21st century.

Therefore, it is essential to not group every immigrant story together — America’s debates around immigration are fundamentally different, often driven by questions of economics rather than criminal or cultural grievances. And here’s where Indian Americans also defy the clichés: in 2023, households headed by Indian Americans had a median annual income of $151,200, notably exceeding the national median for non-Hispanic White households, which stood at $89,050. The picture is just as commanding on an individual level: median personal earnings for Indian-American adults hit $85,300, versus roughly $52,400 for Asians as a whole.

In short, far from being spectators in America’s success story, Indian Americans are writing it — one statistical bracket at a time. Yet, despite their clear contributions, even influential figures like Elon Musk or Vivek Ramaswamy face backlash from the cultural right for asserting that legal, contributing immigrants are as American as anybody else. The uproar says more about insecurity than identity — and the real debate isn’t about who immigrants are, but who gets to belong.

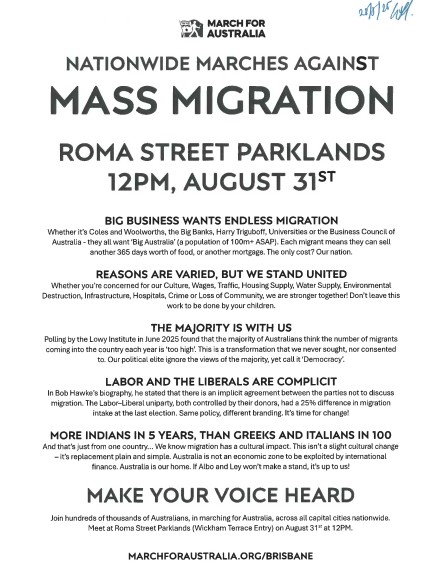

Across the Pacific, Australia has also been shaken by its own wave of anti-immigrant fervor — quite similar in flavor to the anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States. On August 31, under the banner of “March for Australia,” an estimated 52,000 people poured onto the streets in cities such as Sydney, Melbourne, and Perth. What began as rallies framed around concerns over housing shortages, infrastructure strain, and population growth quickly spiraled into something darker.

In many locations, far-right activists, including elements tied to the National Socialist Network, infiltrated the protests, transforming them into breeding grounds for xenophobic sloganeering and occasional clashes. Indian migrants, who have been an intrinsic part of Australia’s skilled workforce and student population, found themselves singled out in the protester’s manifesto sending ripples of unease through one of Australia’s most successful diaspora communities.

The backlash, however, was swift and unequivocal. Leaders across the political spectrum condemned the protests, making clear that such extremism did not reflect the values of a modern, multicultural nation. Home Affairs Minister Tony Burke set the tone when he declared: “There is no place in our country for people who seek to divide and undermine our social cohesion. Nothing could be less Australian.” Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and other senior figures echoed this message, reaffirming the centrality of immigration to the Australian story.

The Indian government, meanwhile, moved quickly to reassure its citizens, with the Ministry of External Affairs emphasizing that the welfare of the diaspora in Australia remained a diplomatic priority. This dual response — domestic condemnation and international vigilance — highlighted both the resilience of Australia’s democratic institutions and the continuing importance of the Indian community in sustaining the country’s prosperity and global outlook.

This is the key distinction that keeps getting blurred: in the UK and parts of Western Europe, the anti-immigrant anger is being driven primarily by specific failures of policy in safeguarding and asylum management, such as, child-exploitation scandals and rows over migrant hotels; whereas in the US and Australia, the temperature rises mostly around economics, borders and housing.

In Britain, a single local crime can nationalize outrage because it lands atop a decade of institutional failings: the Rotherham–Rochdale–Telford scandals; new cases such as the Epping hotel incident; and a sense that authorities tiptoed for years around hard facts to avoid accusations of prejudice. The right approach is to talk accurately about the offender profiles that certain investigations uncovered, and stop laundering specificity into a catch-all term that punishes bystanders.

Meanwhile, the UK’s protest geography — outside asylum hotels — reflects anger at policy choices: prolonged hotel use (tens of thousands still in rooms), opaque local consultations, and isolated but high-salience crimes that become symbols for a system that looks both expensive and unsafe.

In Western Europe, immigration salience tracks asylum surges and security fears: EU first-time asylum applications passed 900,000 in 2024 before easing in 2025; populist parties from Germany’s AfD to France’s RN have converted these concerns into polling gains by linking migration to disorder, housing pressure and national identity. Contrast that with the United States, where the fight is dominated by border metrics and labour markets: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) now touts historic-low encounters after sharp policy shifts, yet the politics remain fierce because voters perceive strain in housing, cities and services regardless of the month-to-month numbers.

Australia sits closer to the US template: the “March for Australia” rallies folded housing and infrastructure anxiety into an anti-immigration message — and were condemned by senior ministers and civil society as divisive and, in parts, hijacked by extremists. Through all of this, one line should be bright: it is essential to not smear Indians (or “South Asians” at large) to avoid naming specific offender cohorts.

The point is to insist on accuracy over euphemism – when authorities are precise about who offends (and where), victims are better protected, offenders face accountability without collective blame, and the public debate stops punishing communities who are largely law-abiding, productive and clearly not the ones agitating for parallel legal orders. Moreover, immigration debates across continents might seem to be similar on the surface, but their roots differ profoundly. What unites them is the danger of lazy generalisations — because when blame is blurred, justice is denied, and the innocent are made to pay for the sins they did not commit.

Contributing Author: Omer Ghazi is a proponent of religious reform and identifies himself as “an Indic Muslim exploring Vedic knowledge and cultural heritage through music”. He extensively writes on geo-politics, history and culture and his book “The Cosmic Dance” is a collection of his poems. When he is not writing columns, he enjoys playing drums and performing raps.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the author’s personal opinions. The Australia Today is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article. The information, facts, or opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of The Australia Today, and The Australia Today News does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Support our Journalism

No-nonsense journalism. No paywalls. Whether you’re in Australia, the UK, Canada, the USA, or India, you can support The Australia Today by taking a paid subscription via Patreon or donating via PayPal — and help keep honest, fearless journalism alive.