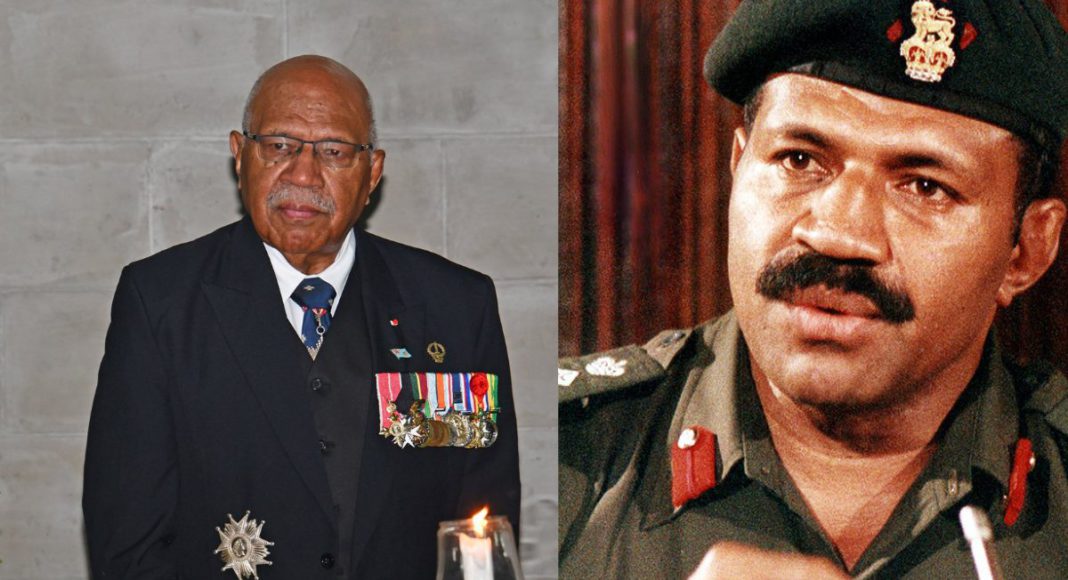

Fiji’s Prime Minister Sitiveni Rabuka has told Fiji’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) that he hopes the new body will help the nation confront its turbulent political history and create space for healing.

Appearing before the Commission, Rabuka said Cabinet had backed a motion to formally support the establishment of the reconciliation body in Parliament. While uncertain about how the process will unfold, he said he is convinced it will help the country confront its past.

“I really believe that it will move the nation. What good? How? I don’t know. But it is an opening for us — for those involved, perpetrators and victims, those who have suffered.”

Rabuka stressed that the Commission must acknowledge not only those directly harmed by political unrest, but also the many people indirectly caught up in the upheavals.

“There are many collateral victims of the events,” he said, noting the wide-ranging social and emotional impact of conflicts over the decades.

He thanked the Commission and expressed hope that the process would give all affected communities a chance to be heard.

As reported by RNZ, Rabuka — the architect of Fiji’s first coups — took the witness stand for the first time, facing an audience both in Fiji and abroad. The TRC, established by his coalition government, is tasked with examining the country’s political crises beginning in 1987.

Rabuka had previously pledged to “voluntarily appear” before the Commission to identify others involved in the two coups he led almost 40 years ago.

Now 77, Rabuka reflected on his early life and the influences that shaped the racial lens through which he justified his actions at the time. He acknowledged being raised in an “insulated” environment — village life, boarding school, and the military — and said he believed he was acting to protect Indigenous Fijians.

Asked whether the coups had served their purpose, he replied:

“The coups have brought out more of a self realisation of who we are, what we’re doing, where we need to be.”

He urged Fijians to stay mindful of “the sensitivity of numbers” and perceptions of imbalance in assets and influence.

In one of the most scrutinised moments, facilitator Netani Rika asked whether removing immunity for coup perpetrators under the 2013 Constitution might prevent future coups. Rabuka responded:

“There should be (a) very objective assessment of what can be done… If that is the will of the people, let it be. At the moment our hands are tied.”

According to FBC News, Rabuka faced questions about human rights violations linked to the 1987 events. He said he regretted what happened but accepted responsibility for setting the stage for what followed.

He insisted he had instructed his commanders to avoid unnecessary force, saying soldiers were issued ammunition but no loaded weapons to prevent harm to civilians.

“My fear was that there would be a breakdown of communication from me to the commanders on the ground and to the soldiers,” he said, describing efforts to ensure discipline and restraint.

He recalled asking his men if they were prepared to fire into a crowd. Some initially raised their hands until he urged them to imagine the person was “a woman” and then “their mother” — at which point every hand lowered.

Rabuka said he was appearing before the Commission because “the truth was also a fact” and he wished to acknowledge the wrongdoing of the time.

As reported by Fijivillage, Rabuka opened his statement with a clear admission: he was “here to confess what happened in 1987 was wrong.”

He said he had a duty to apologise and that those he wronged are entitled to decide whether to accept or reject that apology. His village, still labelled “the coup village,” continues to carry a sense of collective guilt, he said.

Rabuka detailed how his actions had lasting consequences for his family. His daughters lost friends, his wife faced hostility at Lelean Memorial School, and his sisters, both teachers, endured strained relationships.

He also shared personal memories, including throwing away a resignation letter in 1977 when a minority government was unexpectedly endorsed, and later believing there was “no other way” in 1987 — a sentiment he now characterises as part of the pressures of the time.

He acknowledged that the coups triggered a major loss of talent, leaving Fiji with gaps in key professions. One of his responses at the time, he said, was to encourage iTaukei students to pursue studies in law and finance.

The Fiji Sun reported Rabuka’s testimony that his family “suffered directly” because of the coups. He recounted how his daughters faced sudden isolation after arriving at military camp on coup day.

He added that setbacks experienced by his wife and sisters deepened the sense of guilt carried by the family, whose coping strategy had been learning to “get on with life.”

Across his testimony, Rabuka emphasised accountability, remorse, and the hope that the Commission’s work will create space for collective healing — even if the path remains uncertain.

Support our Journalism

No-nonsense journalism. No paywalls. Whether you’re in Australia, the UK, Canada, the USA, or India, you can support The Australia Today by taking a paid subscription via Patreon or donating via PayPal — and help keep honest, fearless journalism alive.