By Narinder S Parmar

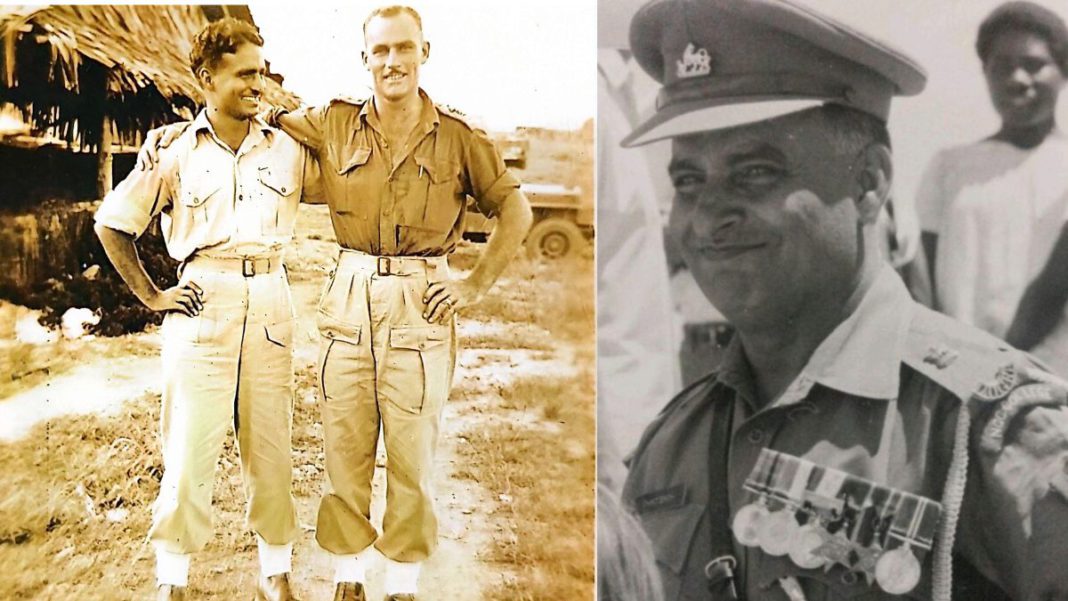

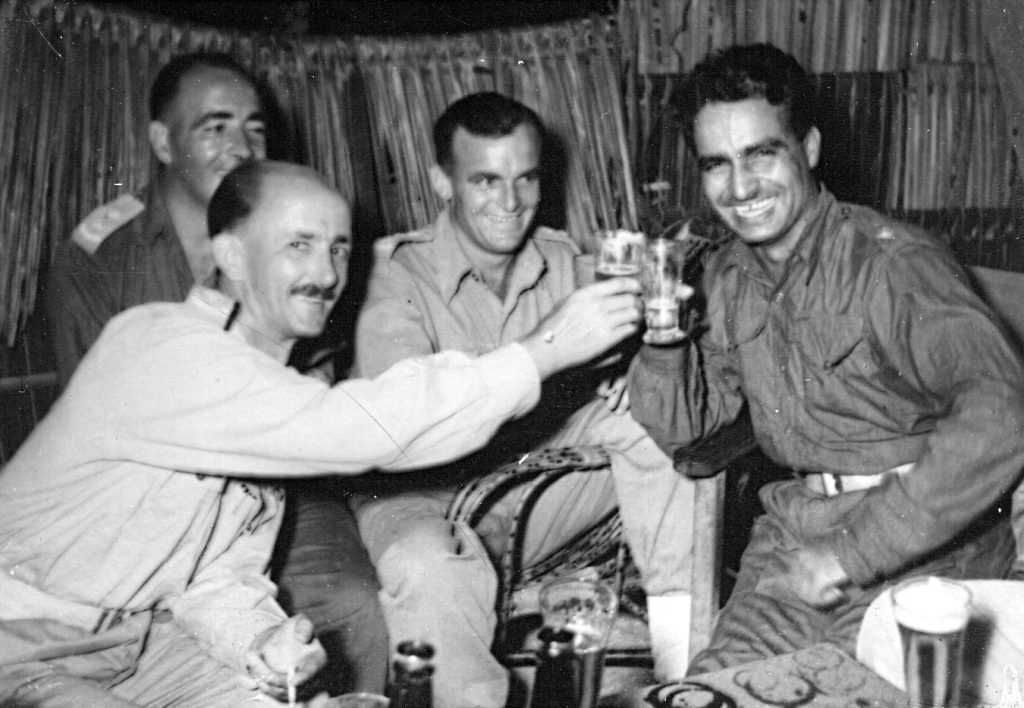

The annals of military history are filled with stories of courage and comradeship, but few are as poignant and enduring as that of my father Major Chint Singh IC5802 of the 2nd Dogra Regiment, whose resilience in the jungles of Papua New Guinea (PNG) during World War II and deep bonds with Australian Defence Forces remain a shining testament to soldierly values.

Enlisted as a sepoy in the 2/12th Frontier Force Regiment (his parent regiment), my father was deployed to Singapore. When the city fell to Japanese forces in 1942, around 3,000 Indian soldiers, taken as prisoners of war, were transported to PNG under harsh captivity.

Among those, only 191 survived the three-year ordeal in the jungle. My father, then a Jamedar, was the sole survivor among the working party of 500 Indian soldiers. His story is one of survival against extraordinary odds, defined by courage, loyalty, resilience, leadership, and an unwavering sense of duty.

After his rescue, Australian forces found that he had recorded crimes committed by Japanese officers and soldiers during his captivity. According to Lt Monk “…on the back of labels from Japanese food tins, on bamboo leaves and on anything else that would support writing.” Subsequently, he was a chief witness against the Japanese officers at the Australian War Crimes Commission at Wewak and Rabaul where he gave powerful testimony about the things he had experienced and seen.

These records, coupled with the testimonies of his experience, highlight the horrific conditions: Indian prisoners subsisted on grass, frogs, snakes, and insects, enduring inhuman treatment and unimaginable hardship. Yet, throughout their captivity, these men upheld the highest virtues of soldiering.

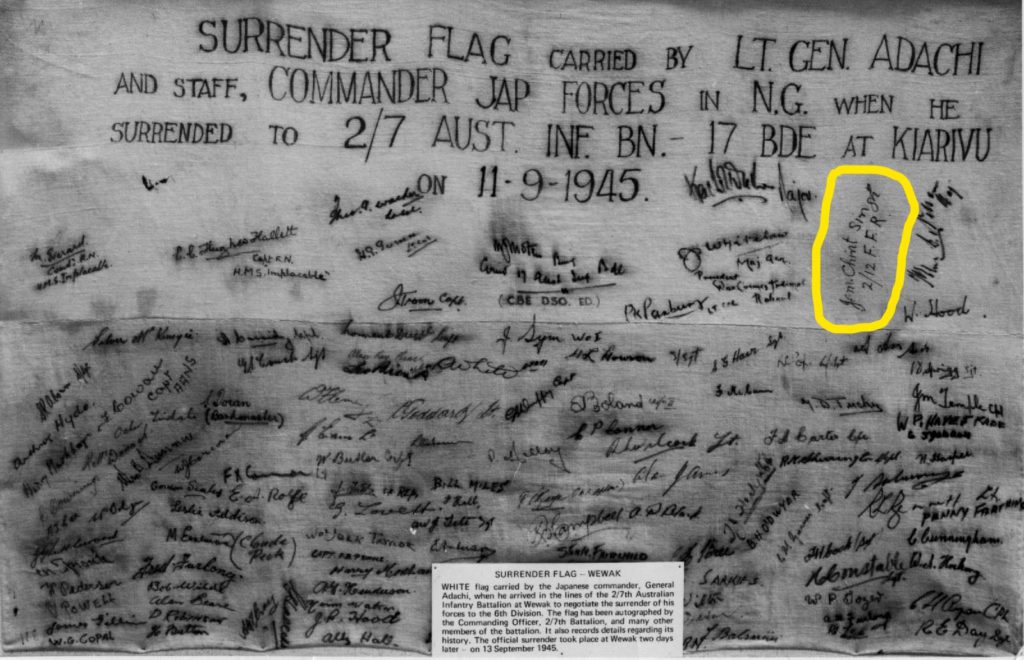

On 30 September 1945, Australian forces contacted the surviving Indian soldiers. Lieutenant F.O. Monk, the first to encounter them, was overcome with emotion when the emaciated soldiers lined up in military formation, saluting him with dignity intact. Soon, they were transported to Wewak by the Australian Navy, and it was during this time that another enduring bond of mateship was born – between my father and Lieutenant Commander Marsden Hordern. Hordern later recounted their first meeting in his memoir, A Merciful Journey.

In Wewak, the Indian soldiers received medical treatment from the 15th Australian Field Ambulance. Sergeant Ron Bader, one of the attending medical staff, took it upon himself to write letters to the families of the Indian soldiers, assuring them that their loved ones were safe and receiving care.

Tragedy struck shortly thereafter. On 16 November 1945, ten of my father’s comrades were killed in a plane crash while en route to Rabaul to board a ship back to India. Lt. Monk wrote to him: “I will never forget the picture of you and your men as you all came ashore at Angoram. It will be with me as long as I live.” This moving reflection encapsulates the profound camaraderie forged in shared adversity.

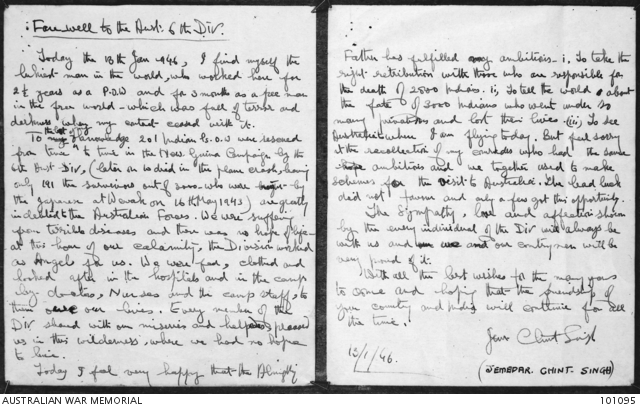

My father, retained as a key witness in the War Crimes Commission, was attached to the 6th Australian Division. There, he shared a tent with Captain Bruce of the 30th Australian Infantry Battalion, further strengthening the bond between the Indian and Australian military personnel. In a farewell letter to the 6th Division in January 1946, he wrote:

“The sympathy, love, and affection shown by every individual of the Division will always be with us, and we and our countrymen will be very proud of it… hoping that the friendship of your country and India will continue for all the time.”

This letter is preserved in the archives of the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Canberra and remains a powerful symbol of wartime mateship.

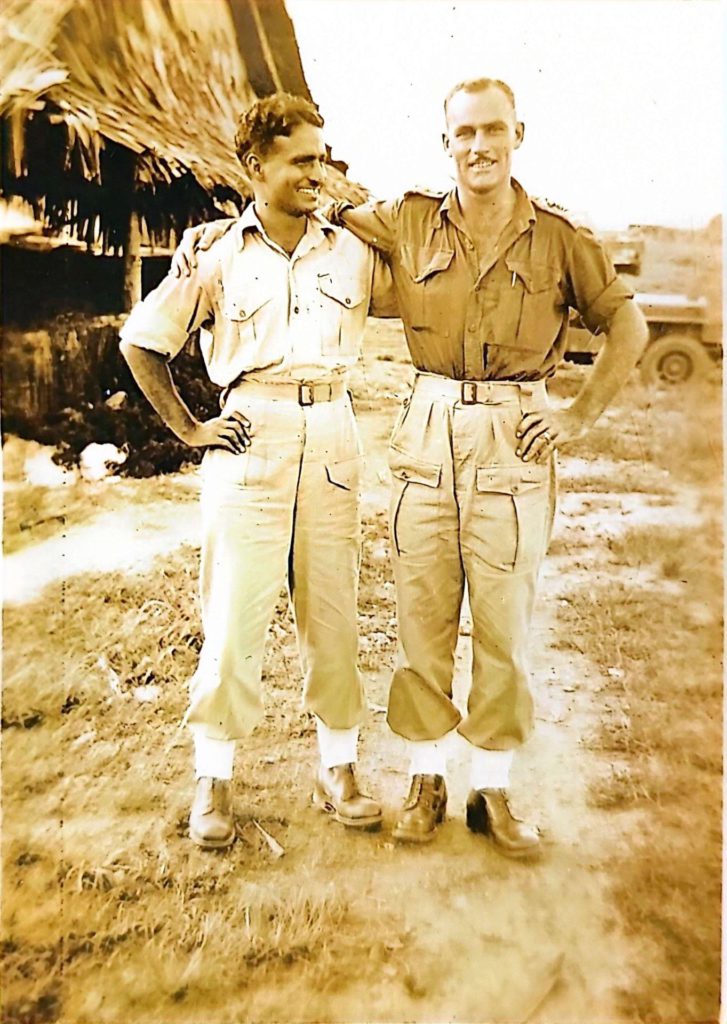

In an extraordinary gesture, the Australian Army invited Major Singh to sign the Japanese surrender flag, now on display at the AWM. This rare honour illustrates the depth of respect he earned among his Australian peers.

His relationship with the Australian Army did not end with the war. In 1947, he was recalled to Australia to provide testimony for the War Crimes Commission. While in Perth, he was hosted by Major General Whitelaw, GOC Western Command, who introduced him to Field Marshal Montgomery, who was visiting Perth at the time.

Later, in 1970, my father was invited by the National branch of the Returned and Services League (RSL) of Australia to attend the 25th anniversary commemorations of the end of WWII, in Wewak, Papua New Guinea (PNG). He received extensive media coverage and spoke on the evolving geopolitical landscape. During the visit, he paid his respects to fallen comrades in PNG war cemeteries and held a solemn remembrance with Lt. Hordern at the Sepik River, where their friendship had begun.

The following year, in 1971, the RSL National Office erected a memorial at Angoram, PNG, in honour of the 2,800 Indian soldiers who perished in captivity. Sadly, this memorial was later destroyed in flooding from the Sepik River.

Among the many Indian POWs, there had been a solemn pact: those who survived must tell the world their story. Major Singh carried that responsibility. Though he passed away in 1983 in a Military Hospital in Lucknow, his family discovered that he had been working on a memoir. A note in his diary instructed the family, “Inform my friends in Australia of the death.” This is a testament of how much he valued his friendship with Australian mates.

In a deeply personal condolence letter, Lt. Commander Marsden Hordern wrote:

“Our friendship commenced in terrible times of cruelty, murder, privation, and suffering, and yet in all this, your father shone out as one of the bright stars of heaven… Because your father was disciplined, intelligent, and courageous, he was never defeated by the most terrible cruelties and because he was a leader of men, he encouraged others to fight against impossible odds.”

“I will never forget our association, and many letters and photographs I have from him are among my most treasured possessions. Many other Australians who knew him in those hard times and since have been enriched by his friendship.”

In 2021, his memoir Maj Chint Singh – The Man Who Should Have Died was published which chronicles not only the harrowing tale of survival but also the enduring spirit of mateship that transcended borders and decades. A revised edition followed in 2023, adding reflections from my mother Kalawati, who lived for more than three years without news of her husband’s fate.

At the end of the war, Sepoy Jai Ram, who died just one day before being rescued, on 29th Sept 1945, said to Major Singh, “Sir, I know I will not see India and the new world, but I am happy now to know we are no longer a prisoner of war. When you reach home, see my parents, and tell them Jai Ram died a peaceful death, and there is no need for them to worry”.

Such lasting words remind us of the Indian soldiers who lived by the core values of loyalty, freedom, justice, duty, honour, resilience, bravery, and comradeship. They stood ready to make the ultimate sacrifice in defence of these ideals. Today, we should bow our heads in a silent prayer for the 2,800 Indian soldiers who never returned to their loved ones.

This story remains a powerful reminder of the price of war, the bonds forged in adversity, and the importance of preserving the legacy of those who endured it. The story of Major Chint Singh and his Australian comrades is not just a historical account – it is a call to remember, to honour, and to never let such courage be forgotten in the jungles of Papua New Guinea. In 2022, I submitted a proposal to the Australian High Commission, New Delhi, to build a monument in Canberra to honour the 2800 Indian soldiers.

Every generation has a moral responsibility to keep these wartime stories and mateship alive. These shared wartime stories, like the one of Major Chint Singh and his Australian mates, form the foundations for building strong bilateral relationships based on mutual respect and trust and enhancing people-to-people contact in various sectors.

Contributing author: Narinder Singh Parmar is Major Chint Singh’s son and a Careers Adviser at Smith’s Hill High School, Wollongong.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed within this article are the author’s personal opinions. The Australia Today is not responsible for the accuracy, completeness, suitability, or validity of any information in this article. The information, facts, or opinions appearing in the article do not reflect the views of The Australia Today, and The Australia Today News does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

Support our Journalism

No-nonsense journalism. No paywalls. Whether you’re in Australia, the UK, Canada, the USA, or India, you can support The Australia Today by taking a paid subscription via Patreon or donating via PayPal — and help keep honest, fearless journalism alive.