A sharp rise in first-year dropouts among international university students is triggering fresh scrutiny of Australia’s international education model, and intensifying a political fight over whether the student visa program is being used as a backdoor work pathway.

New analysis by Menzies Research Centre drawing on federal higher education data shows the national first-year attrition rate for commencing international undergraduate students at publicly supported universities climbed to 17.4% in 2023, up from 9.7% in 2018, equivalent to 14,873 students leaving their university within 12 months of starting.

The most striking figure sits at the top of the table: Central Queensland University (CQ University) recorded a 57.2% first-year attrition rate in 2023, meaning well over half of commencing international undergraduates discontinued their studies at the institution within their first year.

What the data shows, university by university

The same dataset highlights large differences across the sector, with some institutions recording attrition rates above one in three, while others sit below five per cent.

Here are selected first-year international undergraduate attrition rates for the 2023 cohort (with the number of students “attriting” reported alongside):

| University | 2023 first-year attrition rate | Number attriting (2023 cohort) |

|---|---|---|

| CQ University | 57.2% | 616 |

| Flinders University | 44.3% | 354 |

| The University of New England | 45.5% | 71 |

| Australian Catholic University | 34.4% | 878 |

| La Trobe University | 33.5% | 712 |

| Federation University Australia | 36.1% | 238 |

| Southern Cross University | 37.6% | 221 |

| RMIT University | 9.9% | 828 |

| Monash University | 4.8% | 402 |

| The University of Melbourne | 3.6% | 140 |

| The University of Sydney | 4.7% | 213 |

| University of New South Wales | 4.1% | 233 |

The pattern is not simply “more international students equals more dropouts”. Some of the largest universities by international cohort size still record low first-year attrition, while several smaller or regional providers with capital-city campuses record far higher rates.

Why are first-year dropouts rising after arrival?

There is no single explanation, and intent is difficult to prove from attrition data alone. But the main drivers being debated publicly fall into three overlapping categories:

1) Cost-of-living pressure and accommodation shortages

Universities and student advocates have long pointed to financial stress, rental scarcity and the need to work more hours as major factors affecting student persistence — particularly for those arriving into a post-pandemic housing market with high rents and tight vacancy.

CQ University itself has acknowledged these pressures. In its 2023 annual report, the institution said international student retention had declined since the pandemic for reasons including personal financial difficulties, employment opportunities and accommodation shortages, alongside heightened competition and students switching providers early in their studies.

That account matters because it highlights a non-political reality: even “genuine” students can be pushed out of study by an expensive landing and a weak support network, especially in the first semester.

2) Provider-switching incentives and “course-hopping” allegations

A more contentious explanation is that a growing share of students may be enrolling at a university to secure entry, then discontinuing study once they have met minimum requirements — transitioning onto a bridging visa while seeking a cheaper pathway, often in vocational education.

A January 2026 report by the Menzies Research Centre argues the scale, concentration and timing of dropouts “strongly suggest” increasing misuse of the student visa system, particularly at lower-cost providers and capital-city branch campuses.

The report points to a steep increase in people on bridging visas while applying for a new student visa, reporting 107,274 temporary migrants in mid-2025 in that category, up from 13,034 in 2023 and describes long processing timelines that may allow extended work periods while applications and reviews progress.

Separately, public reporting has pointed to the growing load on the Administrative Review Tribunal, including official processing-time reporting indicating migration reviews can take long periods to finalise.

3) Education agent practices and aggressive “poaching”

A third factor sits between student intent and system design: recruitment practices.

The federal government has been moving to restrict incentives that encourage agents to shift students between providers soon after arrival. In 2024, Education Minister Jason Clare outlined legislative changes aimed at improving integrity in the international education sector, including measures that enable a ban on commissions paid to education agents for onshore student transfers.

More recently, reporting indicates the government has moved to prohibit commissions for certain onshore transfers, with the rule flagged to take effect from 31 March 2026.

The policy logic is straightforward: if money changes hands when a student switches providers, it can create an industry incentive to churn students and increase the risk that study becomes secondary to migration or work outcomes.

What CQ University’s 57.2% figure does — and doesn’t — prove

The CQ University rate is so high it has become a headline statistic — but it still needs careful handling.

Attrition measures leaving a provider, not necessarily leaving higher education entirely. Some students may transfer to another university, move into VET, defer for health or family reasons, or return home. Others may have arrived with unrealistic expectations about workload, English-language demands, or the balance between study and earning capacity.

What the data does demonstrate is concentration: a national problem that is disproportionately severe at a subset of institutions. That concentration is central to the policy debate, because it suggests that targeted interventions — rather than blunt caps or reputational damage to the entire sector — may be more effective.

It also highlights risk for universities themselves. International students are a major funding source across Australian higher education, and abrupt disengagement in the first year can destabilise teaching plans, student support services and finances — especially for universities that rely on rapid growth in international commencements.

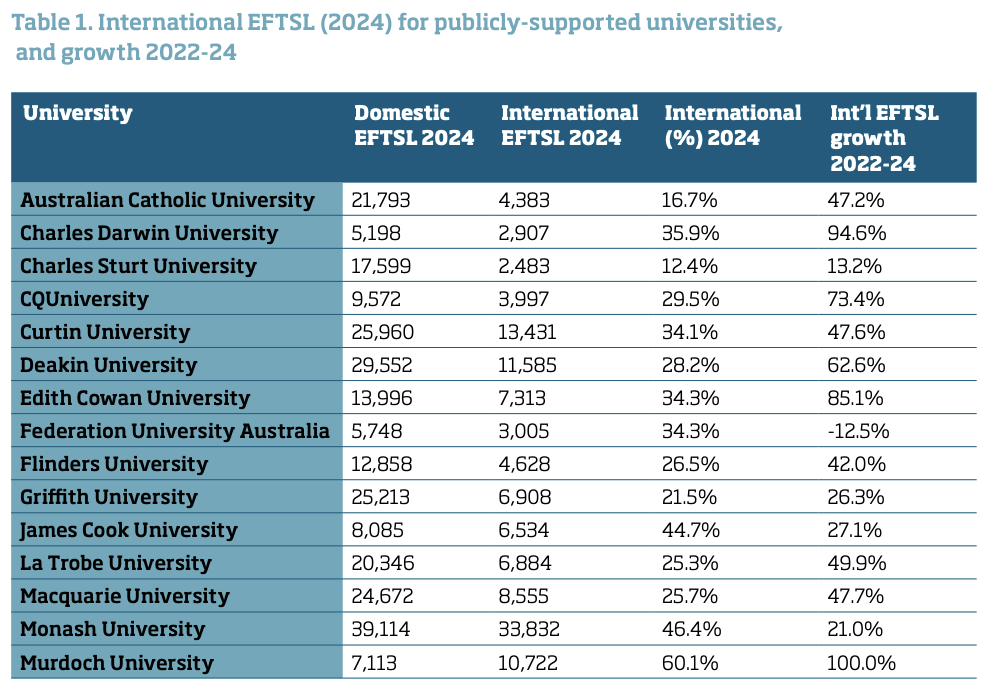

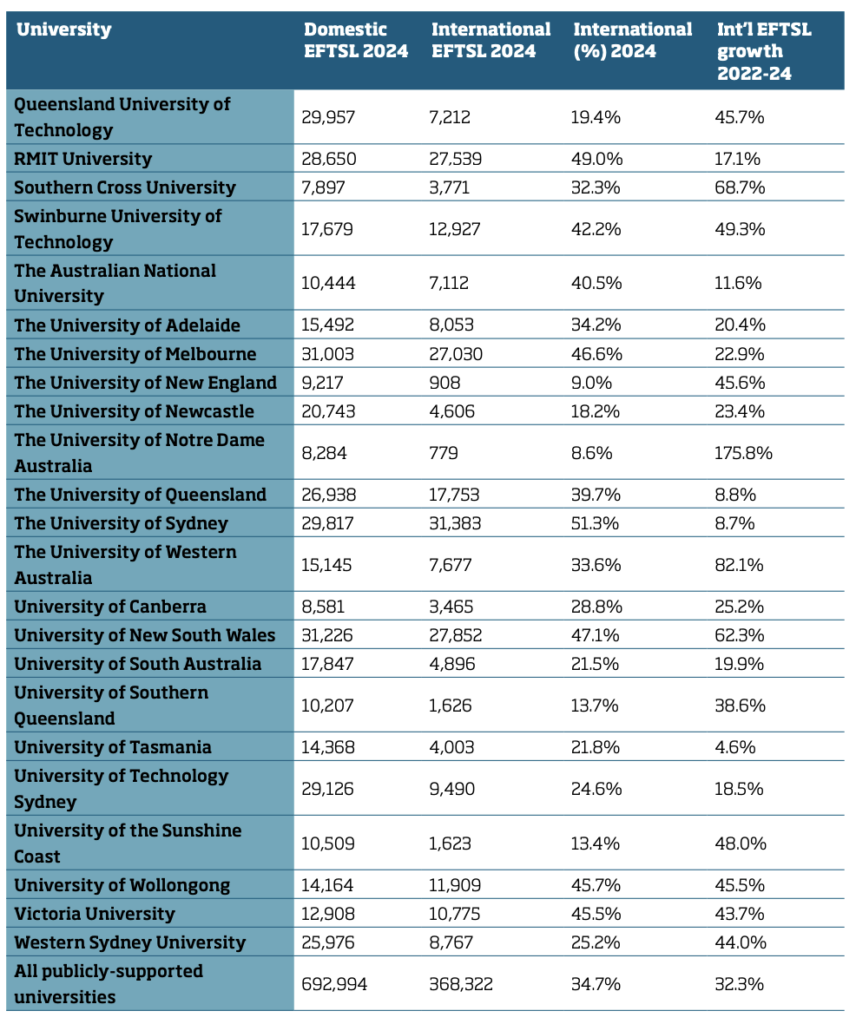

At the same time, Australia’s international student presence is large and growing. Federal higher education statistics show a significant rise in onshore overseas students between 2023 and 2024, and overseas students make up a sizable share of onshore enrolments. That reality increases the stakes: if first-year dropouts keep rising, the reputational and regulatory consequences could extend well beyond a handful of providers.

The policy direction now appears to be moving on two tracks at once:

- Integrity controls, aimed at reducing churn and discouraging visa gaming (including changes affecting agent commissions and provider transfers).

- Student welfare and retention, focused on housing stress, financial hardship and early intervention support — the factors universities themselves cite as key drivers of discontinuation.

Whether Canberra can strike a balance, tightening loopholes without punishing legitimate students, will shape the next phase of Australia’s international education story.

Support our Journalism

No-nonsense journalism. No paywalls. Whether you’re in Australia, the UK, Canada, the USA, or India, you can support The Australia Today by taking a paid subscription via Patreon or donating via PayPal — and help keep honest, fearless journalism alive.